The Making of Blind Pig: Brogue

On October 10th, 2015, The Blind Pig gathered seven chefs from three states for a research dinner on the culture and cuisine of Down East North Carolina partnered with Beaufort Wine & Food. Proceeds supported the local Beaufort chapter of The Boys & Girls Club of Coastal Carolina.

Maxwell Point Harkers island, nc and the back sound

Brogue was literally seven months in the making. It's vision formed from my daft of coastal Carolina and my personal childhood Summers. These Summers involved sandy tobacco fields, swamp and black marsh and a salty ocean. There have been countless memories of fishing pier adventures among Indian Beach with our Uncle Butch. I remember pulling croaker from the waters of Swan Quarter into my grandfathers small vessel ' The Miss Carlie'. There were Summer freshwater fishing trips made on a metal john boat with my father in the great, flat Lake Mattamuskeet. From the coastal tidewater region of Down East to the agriculturally rich and fertile land which reaches the states capital of Raleigh, Eastern Carolina is a beautiful place. All of my formidable and most impressionable food memories were in that place. I had eventually hoped to bring Blind Pig back to this part of the state. This dinner, for me, was a personal dream in the making.

The Summer of 2015 was happily spent with countless trips across the state of North Carolina from the mountains we call home to the ocean in the sea side and historic town of Beaufort, NC. The first on the agenda was to put together a unique team of chefs with respective visions and with a concurrent mission to dig into the present day culture with careful examination of the past in this charming and unique part of Eastern North Carolina. Next, we would dig into local culture speaking with a host of locals from historians, farmers and fourth generation fishermen in order to tie together the roots of this cuisine with an honest effort of authenticity as we could. The roots of history and cultural influence flourish deeply here with the area of European landing and settlement from some of the first discoveries and colonies of the New World. Having ties to Beaufort and Down East for all of my childhood and up through my adult life, I knew that the rich history and culture in this place would set the stage for culinary exploration, especially to certain chefs with a vision.

blind pig family breakfast by travis milton and levon wallace beaufort bordello/admirals house

The Admiral's house, Beaufort, NC Built circa 1883.

hand picked honeycrisp apples from the beaufort farmers market

Eastern Virginia and Carolina native Americans fishing practices with Weir and netting

When Europeans arrived in the late 1500s, North Carolina’s northern Coastal Plain was home to two different cultures of natives Algonkian and Tuscaroran. These natives developed hunting and fishing techniques as well as a diet of wild and foraged foods. Quite simply, the first cuisine of this region was created by these people. Algonkians lived closest to the Atlantic edge, in the Outer Coastal Plain or Tidewater. The term Algonkian isn’t a tribal name; it refers, rather, to the family of languages spoken by tribes who lived from Canada to Carolina. Iroquoian speakers — the Tuscarora, Meherrin, and Nottoway tribes — lived more inland, on the Inner Coastal Plain. The Tuscarora generally lived from just south of the Neuse River to where the Virginia border is today. The Meherrin and Nottoway stayed between the Roanoke and Chowan Rivers. With the arrival of European explorers in the 1500s, two worlds collided in North Carolina. Peoples that had lived here for thousands of years — in a land that had existed for millions — were changed forever, and the stage was set for a new era that would link the peoples and cultures of Europe, Africa, and the Americas.

On April 27, 1584, Captains Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe left the west coast of England in two ships to explore the North American coast for Sir Walter Raleigh. The party of explorers landed on July 13, 1584, on the North Carolina coast just north of Roanoke Island, and claimed the land in the name of Queen Elizabeth. Barlowe wrote that the land they found was:

“Very sandie and low toward the waters side, but so full of grapes as the very beating and surge of the Sea overflowed them, of which we found such plentie, as well there as in all places else, both on the sand and on the greene soil on the hils, as in the plaines, as well on every little shrubbe, as also climing towards the tops of high Cedars, that I thinke in all the world the like abundance is not to be found.”

Croatan Native Americans of Eastern North Carolina Saponi/Mattamuskeet 1585 Voyages of John White Roanoke Island, NC.

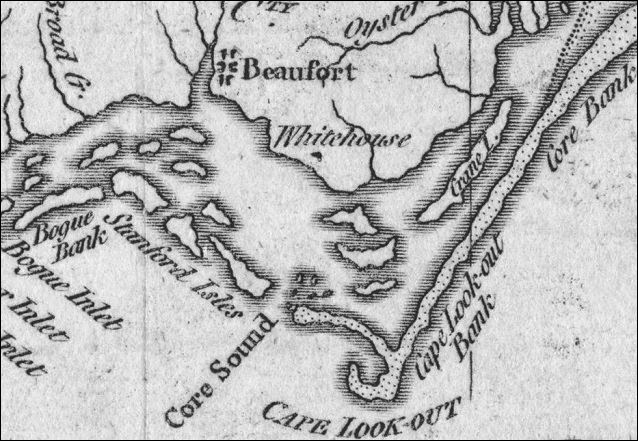

Virginia and Carolina Colonies. John White Exploration map. Circa 1585.

Earlier in the year of 2015, I met Eddie Willis on Harker's Island. It was Eddie's husky demeanor, his sun bleached white hair, the sun wrinkles of his round face and his thick tongue of island brogue which gave me the inspiration for the name of this dinner. Eddie ensured me that chefs would be pleased with what he could show them of the bounty in the waters of Carolina. Eddie also set aside 135 soft shell crab for The Blind Pig which I eventually fried in oyster cracker crumbs and served with fresh tomato and freshly dug potatoes as a third course in the dinner. Eddie is a fourth generation fisherman and his family has lived on Harker's Island since just before the American Revolution. Eddie fishes the same waters as his forefathers and in the same ways with weir as they have passed down through the generations. On the Saturday of the dinner, Eddie would take us out along with his son who is being passed that same fishing heritage of his forefathers. For the chefs to be a part of this heritage was something very special.

Hipster Chefs in One Boat and Hardcore Downeastern Fishermen in the other. Blind Pig brogue

Eddie Willis steers his handmade boat with his son at the front

Seven chefs, their wives and a host of cooks and volunteers joined Eddie and his family on a private tour of the back streams of Harker's Island and into the great waters of the Atlantic along the Cape Lookout National Seashore. It was a drab and dreary Saturday and every chef was under dressed for rain and water works. The boat suffered immensely as it dredged through the rough waters carrying well over 2,000 pounds of men and women which are cooks. After a long ride through choppy, warm water spitting and spraying. I sat (albeit nieve) on the port side edge of the vessel just in front of Levon Wallace who is my size but much taller. Eventually, we had to figure out why we were the only ones getting absolutely drenched from ocean water. It was later, I realized two of the biggest chefs in the group (Levon and I) were both on one side of the boat.

Josh armbruster and mike moore, out at sea, harkers island, nc

We finally reached a row of young gum saplings in the water set out to resemble pickets in the deep blue. Eddie had cut these saplings himself months before from the salt marshes and swamps just as his forefathers had. The gum saplings were sharpened on one end and driven into the sand bottom of the ocean. A hand made hemp-rope net is woven and tied to each pole forming the weir. A weir is a traditional American Indian fishing device, consisting of a trap made of sticks or brush with a large basket in the middle. Weir designs vary according to the location and waters being fished. Typically, setting up a weir involved creating a fence-like structure of reeds, stretching it across a stream, and anchoring it to the bottom by sticking poles into the ground below the water. The reeds were tied together tightly so that fish could swim in, but couldn’t swim out. These weirs were used by the natives prior to European discovery of the land. The very waters we were fishing there in the Atlantic between Harkers Island and Cape Lookout had been fished for thousands of years in the same way as we were experiencing. To pull fish from these waters and cook them in ways of the past was trancendental for us.

Willis Family Gill Nets in the Atlantic Ocean near the cape lookout national seashore.

horseshoe crab being thrown back into the ocean

Young gum saplings are cut from the salt marshes around harkers island by the willis family for four generations. blind pig brogue

Excerpts from John Lawson- A New Voyage to Carolina; Containing the Exact Description and Natural History of That Country: Together with the Present State Thereof and a Journal of a Thousand Miles, Travel'd Thro' Several Nations of Indians. Giving a Particular Account of Their Customs, Manners, &c. (London, 1709) -

'The neighbouring Indians are friendly, and in many Cases serviceable to us, in making us Weirs to catch Fish in, for a small matter, which proves of great Advantage to large Families, because those Engines take great Quantities of many Sorts of Fish, that are very good and nourishing: Some of them hunt and fowl for us at reasonable Rates, the Country being as plentifully provided with all Sorts of Game, as any Part of America; the poorer Sort of Planters often get them to plant for them, by hiring them for that Season, or for so much Work, which commonly comes very reasonable. Moreover, it is remarkable, That no Place on the Continent of America, has seated an English Colony so free from Blood-shed, as Carolina; but all the others have been more damag’d and disturb’d by the Indians, than they have; which is worthy Notice, when we consider how oddly it was first planted with Inhabitants.'

This was a way of fishing passed down through the centuries since the influence of Native Americans on colonists in this part of Carolina. The Blind Pig chefs experienced the harvest and collection of the freshest of fish for our menu. We watched and helped unload horse shoe crab, horny toad fish, flounder, red drum, skate, blue crab, triple tail and pomfret to name a few. These fish were all pulled from the waters alive. What fish are not to be kept are put back in the water alive. This was the sustainable example of fishing of the native Croatan and Algonkian still being practiced by Europeans generations later.

The chefs of Brogue produced seven courses from local and foraged ingredients. Many of the dishes were historic replications of recipes and dishes of that specific region from pre-colonial cooking techniques by fire, colonial recipes and antebellum era cuisine.

The weekend was an incredible experience for chefs meeting and working hand in hand with fishermen and farmers of the region. 138 guests filled the big top tent on Harker's Point in a historic edge of the island overlooking the Back Sound and among the cedars of yesteryear. This part of North Carolina is bountiful with great history and dipped in culture through the ages as this land, state and nation have been formed. It is important to understand food, the people and culture who influence it and most of all where it comes from. This dinner was an outstanding example of introspection from the past with cuisine and giving back to the communities that we have before us in the present. The Blind Pig would like to thank every guest attending which allowed us to be a part of this experiment, it is because of your support that we exist.

Photo by Dan Smith Blind Pig Brogue

Photo by Kim Wallace Blind Pig Brogue

photo by dan smith